By Sheri Norton, GIS Coordinator, Ontario County

Introduction

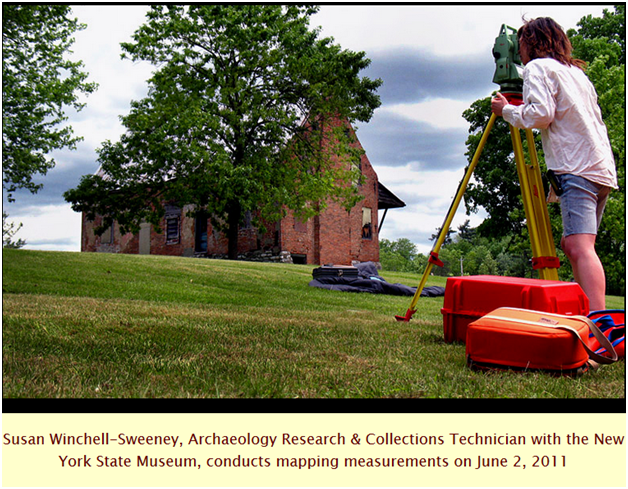

From the early years of archaeology (picture Indiana Jones scrutinizing the 3D city model of Tunis looking for the Arc of the Covenant), maps have played a vital role in recording human history. This is certainly still true today, although modern social scientists such as Susan Winchell-Sweeney can now leverage the wide breadth of tools such as ground-penetrating radar that are non-invasive and therefore help preserve sites for the future.

From the early years of archaeology (picture Indiana Jones scrutinizing the 3D city model of Tunis looking for the Arc of the Covenant), maps have played a vital role in recording human history. This is certainly still true today, although modern social scientists such as Susan Winchell-Sweeney can now leverage the wide breadth of tools such as ground-penetrating radar that are non-invasive and therefore help preserve sites for the future.

Susan holds a Bachelor of Science degree in Interdisciplinary Studies-Archaeology and Soil Science from the State University of New York Empire State College. She has over ten years of archaeological field experience, working at dozens of sites throughout New York State. Her areas of expertise include scientific excavation, artifact identification and analysis, as well as the application of geospatial technologies in archaeological research and cartography. Susan, a GISP, currently works for Underground Imaging Technologies (UIT); is a Board Member of the Harlemville Rural Cemetery Association, Inc.; and is serving her first term as Councilwoman in the Town of Copake.

Interview

Can you describe the ways spatial technology has changed the way you approach your work as an archaeologist?

I have worked primarily to support the research of other archaeologists, and believe the applications of GIS and other “space-based” software and hardware are nearly limitless. The use of spatial technology in archaeology is constantly evolving. When I first started – almost 15 years ago now — the goals and techniques were fairly rudimentary. I employed GIS to produce more accurate, consistent and better-looking maps for archaeological projects. I used mapping-grade GPS units in place of a compass and measuring tape to locate test pits in the field and simply overlaid these locations on georeferenced and digitally-scanned USGS topographic maps. In subsequent projects, I incorporated artifact catalog databases with this same GPS-derived information, and then produced maps which not only identified artifacts, but illustrated their density and where and at what depth they were excavated. This greatly aided in determining the age and what human activity occurred at each project site – whether it was a Native American hunting camp thousands of years old, or a 19th-century freed slave community. Using GIS, I also georeferenced digital historic maps to help target excavations, which saved time and money in the field as well as resulting in greater recovery of archaeological information. More recent studies in which I’ve provided GIS and cartographic support have included a much higher level of spatial analysis and are more regional in geographic extent rather than site-specific. The work has also drawn upon research derived from multiple scientific disciplines, not just that of archaeologists. Some examples can be found online here:

You currently work for Underground Imaging Technologies, LLC. What is a typical day like?

There really is no typical day at UIT, but the job is 100% about spatial relationships! UIT is a digital geophysical mapping firm which utilizes high-technologies like ground-penetrating radar and electromagnetics to detect and locate features underground without excavation. Whether the objects sought are unmarked graves, the buried foundations of long-disappeared historic structures, water utility lines or rebar in concrete highway bridge decks, precision positioning is incorporated in all the data collected. The final “deliverable” for each project includes a georeferenced digital map or series of maps. I’m currently assisting (remotely and virtually, along with colleagues in Alabama and Quebec, Canada) in the mapping of unexploded ordinance (UXO) on a U.S. Army base in western New York that was used in warfare training exercises during the 1940s. The work is both environmental – UXO is the single greatest land contamination issue facing the military in the continental United States – and in an historic sense, archaeological, in nature.

(extracted from the Van Housen House website: http://www.vanhoesenhouse.org/archexcav2011/june_2.html).

As a councilwoman for the Town of Copake, do you find your background in geography and anthropology provides a special perspective for approaching community concerns?

Absolutely – especially in the analysis of human settlement patterns and exploitation of resources. I’m currently serving as the town board liasion to the Town of Copake’s Conservation Advisory Committee. One of the most pressing issues identified by this committee is water quality and supply, which are both greatly impacted by what we do in proximity and use. GIS will be one of the principle tools used by this committee to identify existing water supply conditions and possible future solutions.

What is one of your favorite memories on the job? What made it remarkable?

One of my all-time favorite projects was the preliminary mapping of an archaeological site called Lisnaroo in the Burren region of Ireland. Abandoned as a result of evictions during the 19th-century Great Famine, this village site held the remains of moss-covered stone houses built upon the remains of a much older medieval village. This town, in turn, had been built on the remnants of a prehistoric ring fort or as some Irish people still refer, a “fairie ring.” Not only did the mapping require technologies of great interest to me – GPS, GIS, geophysics and traditional optical survey – the site, surrounded by a forest of hawthorn trees clung with ivy and perched in an eerie, hilly landscape of limestone pavement for which the Burren is renowned, evoked an Ireland of ancient lore. Even my daily commute to the site brought me back to an earlier time; I walked the mile and half each day on a dirt path, past stone walls and grazing cows, following directions which included “turn left by the castle…”

Fun Resources

Cyark (presented at the 2012 Geospatial Summit!)